MICHAEL HEAD PAR EMMANUEL TELLIER

—

M comme Malice. Il y en a (un peu) dans le fait de se lancer dans l’écriture d’un texte consacré au nouvel album de Michael Head en voulant à tout prix éviter la forme classique de la chronique. Mais c’est Pascal Blua qui a demandé, et à Pascal Blua, on ne dit pas non. On dit oui… Mais on ruse un peu.

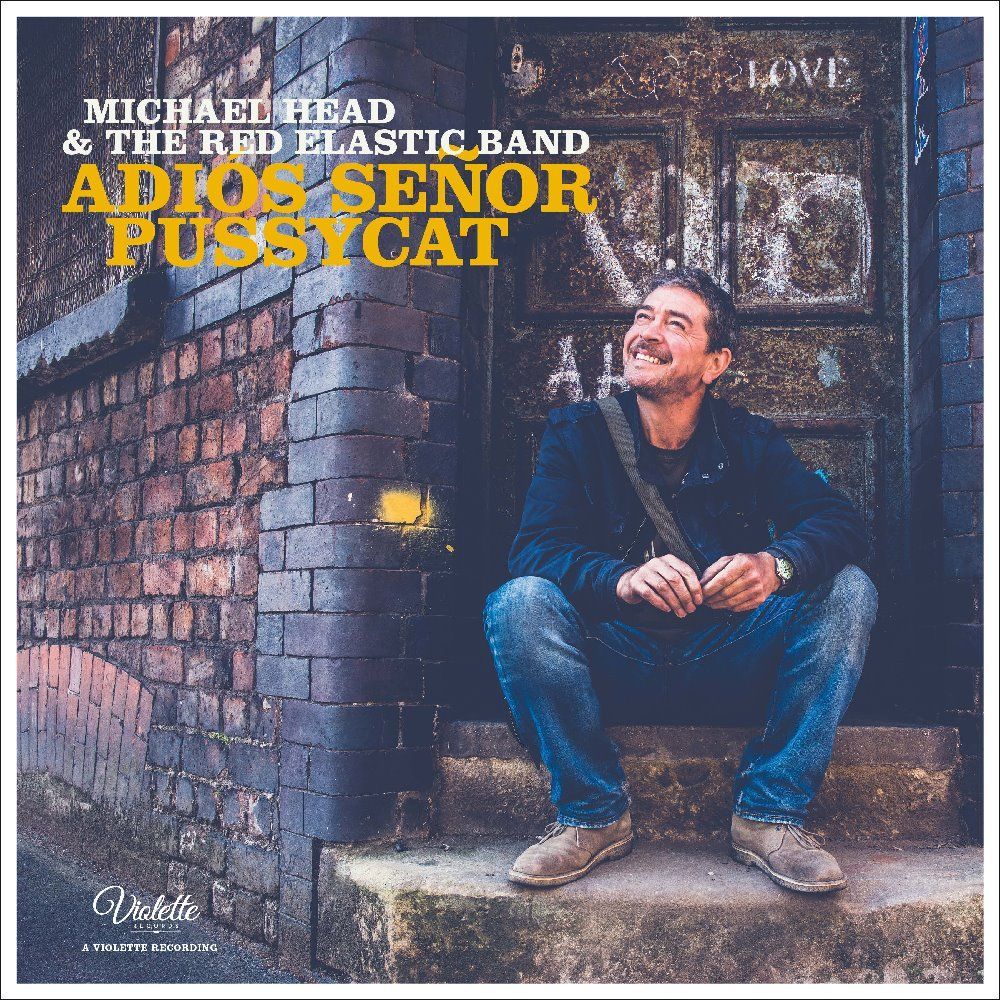

I comme ibérique. Oui je sais, Michael Head vient de Liverpool (pardon, rectification : Michael Head est Liverpool). N’empêche. Il en a toujours pincé pour l’Espagne et l’espagnol. Titres de chansons souvent, titre d’album ici. Pincement du cœur, pincements des cordes. Et peu importe la guitare pourvu qu’on ait l’ivresse… La première chose que j’aime d’amour chez ce drôle de bonhomme (trombine de gavroche cinquantenaire amusé d’être encore tellement en vie sur la radieuse pochette du sus-mentionné Blua), c’est ça, c’est ce côté bohémien, terriblement romanesque : mettez-lui un bout de bois flamenco acheté 40 livres dans une brocante pluvieuse de Sheffield, avec le manche tordu et des auto-collants Sisters of Mercy pour cacher les trous, et l’ex-Pale Fountains se débrouillera toujours pour vous chanter quand même un truc beau comme le soleil, un truc à vous tirer des larmes. Je ne sais pas d’où ça vient, cette “hispanité” des bohémiens de la Mersey. Lee Mavers a la même, John Power a la même, les gringos de The Coral ont la même. Origine mystérieuse mais effet garanti : Michael Head l’ibérique joue des chansons comme Maradona du ballon. Jeu naturel, pas plus réfléchi que ça. Facilité déconcertante, particulièrement dans cette façon de chanter, l’air de rien, la tête dans les nuages. I comme Icare, i comme easy.

C comme (faire plus) court, parce que si j’écris 20 lignes par lettre de son nom, vous n’irez jamais au bout de cette page.

H comme héroïque. C’est quoi, un héros, en musique ? Rayez les mentions inutiles. Un gros vendeur de disques ? (personnellement, je raye). L’auteur forcément maudit d’un ou deux tubes et puis s’en va ? (je raye). Un(e) précoce qui fait tout impeccablement jusqu’à ses 26 ans mais finalement décide de mourir d’une overdose à 27 ans ? (je raye). Ou bien… ou bien (vous me voyez venir) un coureur de fond, un passager clandestin dans l’histoire officielle du rock, rarement sur le pont en plein soleil, mais pas pour autant à fond de cale – quelque part entre les deux, dans son monde à lui, sa « classe à part » ? Paddy McAloon. Edwyn Collins. Peter Milton Walsh. Cette trempe d’hommes. Des vivants, qui n’ont pas oublié qu’il y a avait une vie (parfois cruelle, parfois usante) à côté de la musique… Donc oui, Michael Head est un héros. Qui a toujours fait les choses comme il pouvait. A son rythme. Avec ses moyens du moment, sa modestie parfois, ses gueules de bois. Mais aussi avec sa capacité à se relever, à refaire la paix avec la musique, avec l’idée d’être entendu, écouté, apprécié. Un honnête homme. Imparfait, mais entier. Et qui se permet ajourd’hui de mettre à peu près toutes les meilleures chansons de sa livraison 2017 à la fin de l’album en question. Et pourquoi pas après tout ? C’est qui le patron ?

A comme acoustique. Encore et toujours la base de tout. Un homme, sa guitare acoustique, le canapé, la télévision en fond sonore, le chat qui passe, accross the kitchen table. Un jour, chanson. Un jour, pas chanson. Pas grave, ça ira mieux demain… Savoir y revenir. En rêver la nuit. Oublier. Se rappeler. Oublier à nouveau. Commencer à trier. 5 chansons, 6 chansons… Et puis un jour, peut-être, ça fait un disque. Est-ce qu’on demandait à Maradona d’aller s’entrainer ? Non, il allait jouer au foot. Est-ce qu’on demande à Michael Head d’enregistrer un album ? Non, il joue de la guitare devant sa télé. Jusqu’au jour où.

E comme éternel. Pas certain qu’il le sache lui-même, mais la presse anglaise, généreuse ces jours-ci, semble enfin décider à lui dire (fucking pas trop tôt, les gars !!!) : oui, Michael Head a conçu, depuis le début des années 1980, une œuvre discographique qui a un incontestable parfum d’éternel. Depuis les Palies, depuis Shack, Head est dans cette cour-là, au milieu des très grands. Par la finesse extrême de ses entrelacs mélodiques, par le naturel désarmant de sa voix (cadeau divin), par son hispanité mêlée de crachin anglais, la souplesse toute latine des rythmiques qui lui viennent dès qu’il prend sa guitare. Head habite parmi les éternels. Le Jimmy Webb de Wichita Lineman (immortalisée par Glen Campbell). Le Scott Walker de The Seventh Seal. Le George Harrison de Something. Le Mac Davis de In The Ghetto (sublimée par Presley). Exagération ? Emportement coupable du fan qui ne se contrôle plus ? Je ne crois pas… Faut-il redire ici qu’il est crucial (en 2017 probablement plus que jamais) de distinguer les chansons (leur structuration, leur mode opératoire, leur charme intrinsèque) des interprétations plus ou moins éloquentes, flatteuses, tapageuses ou au contraire modestes qu’en feront plus tard leurs interprètes ? Ne jamais confondre le bois de la table et le vernis qu’on met dessus. Un exemple au hasard : Reflektor, d’Arcade Fire. Est-ce une grande chanson ? Je ne crois pas. Au mieux c’est un gimmick, un bout d’idée. Est-ce un bon titre une fois accouché, produit, gonflé aux hormones pro-tools et claps-claps electro ? Oui. Un exemple en sens inverse ? Velocity girl de Primal Scream. Un joyau brut, mais saboté en 85 maigres secondes d’un non-mix potache sous intra-veineuse Byrdsienne. Dommage (un peu) pour nos oreilles… mais ça n’en reste pas moins une géniale chanson… Vous pensez que je m’égare ? Quel rapport avec Michael Head ? Eh bien cet homme-là a su allier les deux (la puissance de la chanson, la pertinence de l’interprétation) pendant l’essentiel de sa carrière – et notamment quand il travaillait avec son frère John, qu’on regrette d’ailleurs de ne plus entendre apporter ses contre-champs lumineux à la 12-cordes électrique. Les Pale Fountains avaient cette qualité rare : ils écrivaient mieux que personne au monde des chansons des Pale Fountains, et en plus, ils les enregistraient avec une éloquence, une vista, une autorité naturelle que personne d’autre n’aurait pu approcher. Comme les Smiths. Comme les Woodentops. Comme Echo and the Bunnymen. Or, me semble-t-il, Michael Head a plutôt su garder cette double compétence peu fréquente : être à la fois le géniteur et l’accoucheur. Le bois de la table et le vernis.

Ici, ce miracle d’équilibre s’entend en particulier sur des titres comme Picasso et 4&4 still makes 8, qui ont comme point commun d’avancer tout droit, par la grâce d’une grosse caisse de batterie simplissime, un truc à faire marcher les enfants face au vent un jour de kermesse. C’est très basique, mais ça marche merveilleusement bien, car alors Michael Head peut laisser couler sa voix au naturel, et nous prendre in the palm of his hand avec les modulations de voix et subtiles développements de mélodies dont il a le secret. Aux premières écoutes, cela semble fonctionner un peu moins sur des titres comme Overjoyed ou Queen of all Saints, construites sur des rythmiques ternaires. Ça peut être un piège, une valse. Ça peut enfermer la voix dans des espaces réduits, faute de place disponible, faute d’oxygène. Au premier couplet de Josephine, on a peur pour la suite : que va bien pouvoir faire Michael Head de ce balancement pas original pour deux pence, de cette mélodie de chant plate comme une piste d’aéroport ? Et puis arrive le refrain, et là, c’est baroque around the clock, poussez les tables et faites entrer les joueurs de fifres. Preuve que ça peut être formidable, aussi, une valse ; et que Michael Head maitrise aussi bien l’écriture que la mise en scène. Comme on dit à Liverpool : BOSS.

L comme légèreté. Au sens de retenue, de délicatesse. De frisson dans la voix. Winter turns to spring est tout cela, et c’est une percée de bleu clair bienvenue dans un ciel ailleurs un peu trop chargé à mon goût. Head et un piano, that’s all. Head qui chante (un peu) comme Edwyn Collins, la voix au bord des larmes, au bord de cette soul mélancolique et noctambule qu’on joue dans les juke-box de Memphis quand les derniers clients sont partis se coucher. Et l’auditeur innocent que nous sommes se retrouve pris au piège, obligé de détourner pudiquement le regard quand l’autre personne dans la pièce dit : « ça va ? t’as l’air ému…?» (tu m’étonnes).

Fantasme pour aujourd’hui et demain : entendre Michael Head (et Peter Walsh, et Neil Hannon, et quelques autres encore) s’offrir le merveilleux plongeon dans l’ascèse et la nudité instrumentale que s’est offert Paddy McAloon lorsqu’il a rejoué l’essentiel de Steve McQueen à la guitare acoustique il y a quelques années (chef d’œuvre diabolique). Appelons-ça le « traitement-Johnny-Cash-American-Recordings ». Passé 50 ans, ça devrait être obligatoire et remboursé par la Sécurité Sociale. « Tiens, Michael, voilà ton billet d’avion : tu pars quinze jours chez Rick Rubin, tu t’inquiètes pas, il t’expliquera…»

H comme HMS Fable. Ou Here’s tom with the weather… A toi, jeune internaute qui passe ici un peu par hasard (ou erreur), les vieux gars comme Pascal Blua et moi te disent que tu dois aussi t’intéresser à la discographie antérieure de Michael Head. Non mais.

E comme évidemment. Evidemment Workin’ family. Evidemment Rumer. Evidemment Wild Mountain Thyme. Evidemment les Byrds, évidemment Love, évidemment Shack période Zilch (tellement sous-estimé, ce disque). Ces titres-là sont la chair, l’âme, le sang et les larmes d’Adios Senor Pussycat. Michael Head dans un miroir face à lui-même, les yeux grands ouverts. « Oui, j’ai vécu tout ça… Oui, je suis toujours là…» Michael Head ? An absolute NON beginner, qui a pourtant gardé tout le charme innocent de sa brillante jeunesse. Ça se fête, non ? Alors sur le sublime Rumer, il a invité des copines pour faire des choeurs très coeur (avec les doigts), façon Leonard-Cohen-part-faire-du-surf-à-Malibu. Et du coup elles sont restées chanter sur la très californienne et non moins réjouissante Wild Mountain Thyme. Merveilleuse fin d’album.

A comme Adios Amigo. Quoi, c’est déjà fini ? Alors vivement le prochain album. (Nota bene : m’est avis que Michael va les enchaîner dans les années qui viennent, et qu’ils vont se vendre de mieux en mieux, juste retour des choses). En attendant, soyons clairs : celui-là est somptueux. Je déteste les notes, mais puisque vous insistez : 9,37 sur 10.

D comme Disquaire, Demain, Direct, D’accord ?

Emmanuel Tellier

20 octobre 2017

MICHAEL HEAD BY EMMANUEL TELLIER (1)

—

M is for mischief. There’s (a bit) of that in the mere fact that I’m sitting down to write something about the new Michael Head album but a conventional review is the very last thing I feel like doing. Still, Pascal Blua asked me to do it and you don’t say “no” to Pascal Blua – you say “yes”, you just need to be a bit crafty about it.

I is for Iberian. Yes I know, Michael Head comes from Liverpool (sorry, my mistake – Michael Head is Liverpool). Even so, he’s always had a thing about Spain and Spanish – often it’s in the titles of songs, but this time it’s the album itself. When you’re plucking the (heart) strings, it doesn’t really matter what guitar you use as long as you can feel that exhilaration… That’s the first thing I love about this rather odd bloke (looking like a fifty-something street urchin, looking amused at still being alive on the radiant sleeve designed by the aforementioned Mr Blua), his bohemian and incredibly romantic side – just give him a cheap flamenco guitar picked up from a rainy Sheffield flea market for 40 quid, with a twisted neck and Sisters of Mercy stickers hiding the holes, and the former Pale Fountain will still manage to sing you something as gorgeous as the sun that’ll reduce you to tears. I don’t know where this Hispanic thing all the Mersey bohemians seem to have comes from – Lee Mavers has got the same thing, so has John Power, so have the gringos from The Coral, but wherever they get it from, it never fails – Michael Head the Iberian plays songs the way Maradona played with the ball – naturally, without even thinking about it. There’s a disconcerting ease, especially in the way he sings, as though it didn’t matter, with his head in clouds. I is for Icarus and it’s as easy as A-B-C.

C is for cutting it short, because if I write 20 lines for each letter of his name you’ll never get to the end of the page and Pascal Blua won’t like that.

H is for heroic. Just what is a musical hero? Delete all that do not apply. Is it someone who sells loads of records? (I’d delete that one myself). Is it a tortured soul who writes a couple of hits and then does one? (I’d delete that as well). Is it a precocious type who doesn’t put a foot wrong up to the age of 26 but ends up deciding to die of an overdose at 27? (That’s another one I’d cross out). Or else… Or else (you’re way ahead of me) is it a long-distance runner, a stowaway in the official history of rock, rarely found sunbathing up on deck but not actually hidden away at the bottom of the ship’s hold – someone who’s somewhere between the two, in his own world, in a “class of his own”? Paddy McAloon. Edwyn Collins. Peter Milton Walsh. People like that. These are survivors, who haven’t forgotten that there’s a life (though it may sometimes be cruel and sometimes exhausting) outside music… So, at the end of the day yes, Michael Head is a hero. He’s someone who’s always done the best he could – but at his own pace, and with whatever he happened to have at the time, sometimes drawing on his modesty or his hangovers, but sometimes using his ability to pick himself up again, to make peace again both with music and with the idea of being heard, listened to and appreciated. An honest man – imperfect but with his integrity intact. He’s now allowed himself to put nearly all the best songs on his 2017 album right at the end – and, after all, why shouldn’t he – who’s the boss here?

A is for acoustic. This is still the basis of everything, just as it always has been. A man, his acoustic guitar, the sofa, the television in the background, a passing cat, Across The Kitchen Table. One day a song might come along, the next day it might not. Still, never mind, things’ll be better tomorrow… You need to know how to come back to it. You need to dream about it at night. Forget. Remember. Forget again. Start picking out the good ones. Five songs, then six… Then one day maybe you’ve got enough for a record. You don’t think they used to ask Maradona to go and train, do you? Of course not. He went off and played football. So nobody’s going to ask Michael Head to record an album, are they? Of course not. He’ll sit and play the guitar while he’s watching the telly. Until, one fine day…

E is for eternal, as in timeless. I’m not sure he knows it himself, but the British press are feeling generous nowadays, and they seem finally (and not a fucking minute too soon, lads!!!) to have decided to inform Mr Head that, since the early 1980s, he’s been assembling a back catalogue with an unmistakeable whiff of the timeless about it. Since the Paleys, since Shack, Head has been right up there with the very best. It’s in the incredibly delicate way he weaves his melodies, his disarmingly unaffected voice (a gift from the gods), his combination of Spanish sun and English drizzle, the very Latin suppleness of the rhythms that come along the minute he picks up his guitar. Head is up there with the timeless artists. The Jimmy Webb of Wichita Lineman (immortalised by Glen Campbell). The Scott Walker of The Seventh Seal. The George Harrison of Something. The Mac Davis of In The Ghetto (performed sublimely by Presley). Do you think I’m exaggerating? Am I just a fan getting guiltily carried away? I don’t think so… Do I need to repeat here that – in 2017 probably more than ever – it’s crucial to make a distinction between the songs (the way they’re structured, the way they work, their intrinsic charm) and how performers may approach them later on, which can vary in terms of how articulate, flattering, ostentatious or, on the contrary, modest they are? Never confuse the wood from which a table is made with the varnish on top of it. Here’s a random example: is Arcade Fire’s Reflektor a great song? I don’t think so. At best it’s a gimmick, a fragment of an idea. Is it a good track once it’s been laid down, produced, beefed up with Pro Tools steroids and electro handclaps? Sure. OK, then what about an example of the same thing the other way around? Take Primal Scream’s Velocity Girl, that’s an unpolished gem, but messed up by an 85-second schoolboy non-mix on a Byrdsian IV drip. It’s (rather) a shame when you listen to it… but it’s still a fantastic song… OK, OK, so you think I’m rambling, do you? What’s all this got to do with Michael Head? Well, this bloke has managed to combine the two (the power of the song and the right performance) throughout most of his career – and especially when he was working with his brother John, it’s a shame we no longer hear his chiming electric 12-string counterpoints. The Pale Fountains had that rare quality – they wrote songs Pale Fountains better than anyone else in the world, and they also recorded them with an eloquence, an outlook and a natural authority that nobody else could’ve got near. Like The Smiths. Like The Woodentops. Like Echo and the Bunnymen. Even so, it seems to me that Michael Head has more or less managed to retain the unusual twofold skill of being both the parent and the midwife. The wood from which the table is made and the varnish.

Here, you can hear this miracle of balance particularly on tracks like Picasso and 4&4 Still Makes 8 – what they have in common is that they move straight ahead, driven by an incredibly simple great big bass drum, the kind of thing you need to get reluctant children marching into the wind on a church outing. It’s very basic, but it works wonderfully because it means Michael Head can let his voice flow naturally, picking us up in the palm of his hand with those vocal modulations and subtle melodic developments that only he knows how to pull off. On the first few listens, it doesn’t seem to work quite as well on tracks built upon compound rhythms such as Overjoyed and Queen Of All Saints. A waltz can be a trap – it can hem the voice into small spaces, where there’s not enough room or oxygen. When you hear the first couplet of Josephine, you’re afraid of what’s coming next – what can Michael Head possibly do with this hackneyed tuppenny ha’penny swaying rhythm and a vocal melody that’s as flat as an airport runway? Then comes the chorus, and it’s baroque around the clock, push back the tables and bring in the fife players, proving that a waltz can be amazing too; and that Michael Head is as good at writing as he is at directing. “Boss”, as they say in Liverpool.

L is for lightness of touch. In the sense of restraint and delicacy. A shiver in the voice. Winter Turns To Spring is all of this, and it’s some welcome light blue breaking through a sky which is rather too overcast for my taste. It’s just Head and a piano. Head sings (a bit) like Edwyn Collins, his voice welling up, bordering on the kind of melancholic, late-night soul that’s played on jukeboxes in Memphis when the last customers have headed off to bed, and the innocent listener is caught in the trap, forced to look discreetly away while the other person in the room says “are you OK? You look a bit upset…” (who’d’ve thought it).

A ghost for today and tomorrow – hearing Michael Head (and Peter Walsh, and Neil Hannon, and a few others) indulging themselves with a wonderful dive into asceticism and instrumental nudity, of the kind Paddy McAloon allowed himself when he reinterpreted most of Steve McQueen on acoustic guitar a few years back (an uncanny masterpiece). Let’s call it the “Johnny-Cash-American-Recordings treatment”. Once you get past 50 it ought to be compulsory and you ought to be able to claim the cost back from the Social Security. “Hey, Michael, here’s your ‘plane ticket – you’re off to spend a fortnight at Rick Rubin’s place, don’t worry, he’ll tell you what it’s all about when you get there…”

H is for HMS Fable. Or Here’s Tom With The Weather… It’s up to young Web users like you who’ve come across this page more or less by chance (or by mistake) but take it from old blokes like Pascal Blua and myself, you really should check out Michael Head’s back catalogue. No really, go on…

E is for evidently or, to put it another way, obviously. Workin’ Family obviously. Rumer, obviously. Wild Mountain Thyme, obviously. The Byrds obviously, Love obviously, Zilch-period Shack obviously (such an underestimated record). These tracks are the flesh, the soul, the blood and the tears of Adios Senor Pussycat. Michael Head looking at himself in a mirror, his eyes open wide. “Yes, all that happened to me… Yes, I’m still here…” Michael Head? He really ISN’T an absolute beginner, even though he’s managed to hang onto all the innocent charm of his brilliant salad days – that, surely, is something to be celebrated, isn’t it? Then, on the sublime Rumer, he’s got some lady friends in to do some gorgeous (and very catchy) Leonard-Cohen-goes-surfing-in-Malibu-style backing vocals and, as they were there, they hung around to sing on the very Californian and no less delightful Wild Mountain Thyme, which is a wonderful way to finish an album.

A is for Adios Amigo. Eh? That’s it? Already? Well, roll on the next album. (N.B. I reckon Michael’s going to be releasing one record after another over the next few years, and they’ll get better and better, which’ll be only right and proper). In the meantime, let’s get this straight, this one is fabulous. I hate scores but, if you insist, 9.377 out of 10.

D is for do it – get yourself straight down to your local record shop tomorrow, OK?

Emmanuel Tellier

October 20th 2017

—

CREDITS

A huge thank you to our friend Nick Halliwell for the english translation.

Emmanuel Tellier is a french journalist.

Photography by John Johnson